One who pays the piper calls the tune. More so in the corporate world, where investors rule the roost. It is no different with sustainability reporting, where the investors call the shots.

Starting with ethical investing in the initial stages, to ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investments in the later stages, sustainability reporting assumed increasing importance with change in the profile of investors. The advent of pension funds and life insurance companies as investors, resulted in evaluation of investments on a longer time horizon as their investment outlook was for more than ten years.

In contrast to short-term investor like mutual funds who look at profits, long-term investors like pension funds and insurance companies began to look at sustainable profits, i.e. not just financial profits but also the social and environmental impact caused by the operations of the company.

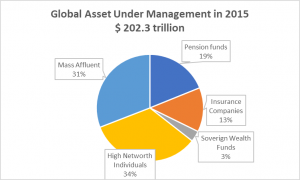

With every increase in the size of pension funds and insurance companies, the importance of sustainability report too grew in tandem. As of 2015, Pension fund accounted for 19% and Insurance companies accounted for 13% of the Global Asset under Management which was of $202 trillion.

The Concept

A business operates in the society and the society is embedded in the nature, is a truism that investors were forced to confront with in the last two decades of the 20th century. They saw financially successful businesses come to a grinding halt triggered by an environmental disaster or a social outrage caused by its operations.

Profit like speed is unidimensional; investors, once they realized that they were investing in the company for the long haul, had to look beyond profits and look at sustainable profits. The realization that companies are running a marathon and not a sprint is what prompted the long-term investors to look at the ‘health’ and ‘stamina’ of the ‘athlete’. For businesses, health and stamina crudely translate to their environmental and social impact.

The Bhopal Gas Tragedy in the factory premise of Union Carbide in 1984, soon followed by Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 made the business world confront the risk of environmental factors. Likewise, large sections of customers boycotting goods produced in sweat shops of the less developed countries around the world dented major consumer brands, thereby highlighting the risk of social practices prevalent in the supply chain of large companies.

Sweat shops is not a new phenomenon as it was a term used in the 19th century for goods produced in inhuman conditions of factories where an employer violated the laws governing minimum wage and overtime work or engaged child labour or disregarded occupational safety and health safeguards to earn profits. The outrage and legislations banning such practices in the developed countries pushed these exploitative industries to the less developed countries in Asia and Africa away from the line of sight of the US and European customers. An unintended consequence of globalization in the 1980s was the focus that fell on these hidden sweatshops.

The First of First

STEAG, a major German utilities company for the first time in the business year 1971-72, published a Business-social report in their Annual report.

Building on the initiative of STEAG, a working group of thirty German companies in 1977 formed the Social Accounting Practice. This group recommended an integrated multifaceted approach to reporting. Their recommendation consisted of the Social report, Value-added accounts, and Societal-impact accounts.

The Social report was a qualitative, thematic description of the objectives, measures, output and effect of the company’s social objectives. Value-added account, computed the distribution of value added by the company in the previous year by its various constituents. The Societal-impact account tabulated the company’s socially related expenditures and its directly calculable socially related revenues.

While these initiatives flowered on the German side, in France, Sudreau Report commissioned by Government of France was published in mid 1970s. This report mandated the preparation of a Social balance sheet. This report initially was only for large French companies in 1977.

Gradually the concept expanded to a more comprehensive requirement of accounting for all aspects of social costs. This movement is best summed up in the words of Courtney C Brown, in his book, Beyond the Bottom line, ‘from an organization conscious of a single purpose (profit), to one conscious of a multiplicity of purpose (economic, social, psychological, educational, environmental and even political).’

In India too, the requirement to account for social costs emerged in 1988. The mandate was to report on Conservation of energy, technology absorption, and research and development activities in the Directors report. While only the bare minimum is mandated, global initiatives for voluntary disclosures are substantial and extensive. Triple Bottom Line Initiative and reporting (TBL), AA1000 standard on social and ethical accountability and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), to name the three, are among the more prominent initiatives. TBL describes the concept of social and environmental costs, AA1000 is an international standard for corporate social responsibility management and GRI defines a framework for reporting.

Mainstreaming Sustainable Reports

The Vietnam war of late 1960s triggered ethical investing when peace loving investors wanted to abstain from investing in armament companies and thereby indirectly supporting the war. Soon thereafter, issues of social importance entered the investors’ concerns, when investors boycotted companies that operated in the morally repulsive apartheid practices legally enforced in the Republic of South Africa.

Ethical investing highlighted the power of investors in shaping the way societies functioned. In early 1990s, as the cost of Benefit Defined Pensions schemes spiralled due to longer life spans of the pensioners and lower interest rates earned on the corpus set aside for making these pension payments, they were replaced by Contribution Defined Pension schemes. In Contribution Defined Pension schemes employees took charge of their own pension funds and started opting for equity investments to get higher returns. With pension funds, the investment horizon was a few decades, requiring these investors to look at not just profits but sustainable profits which is a factor of social and environmental impact of the companies’ operations.

With time, the investors expanded their scrutiny beyond the companies’ operations to their suppliers and partners bringing in a wave of sustainability reporting.

As the proportion of investments managed by the pension funds and insurance companies increased, sustainability reports moved from being a differentiator to becoming an essential reporting requirement for all large companies.

Sustainability Reports in India

Sustainability Reports have limited presence in the Indian corporate world, being limited to industries like IT Services which deal with international clients who make it an essential criteria or environmentally hazardous industries like mining, tobacco and paper products.

SEBI has mandated a diluted form of sustainability reporting by requiring the top 500 companies by market capitalization to have Business Responsibility Reports. However, most investors in India have not used sustainability reports as an essential input in making their investment decisions. This position can and should change with the growth in investment corpus available in National Pension Scheme where the investor is investing for an average tenure of 10-15 years if not more.

Given this longer time horizon, there is no option for the Indian pension funds but to look at businesses that are running the marathon and ignore those who are engaged in short sprints of quarterly or annual profits.